Get in Touch

Email Address

Info@rhino.com

Phone Number

Sales: +098 765 4321

As Marine Ecology Interns, we have spent the last few weeks alternating between the classroom and the ocean, learning about fish and coral identification, their importance in ecosystems, and how we can protect and preserve our incredible reefs. We have participated in many clean-up dives, biodiversity assessments, and removal of certain species threatening coral health and growth, such as drupella snails and the crown of thorns starfish.

One of the more difficult skills for me to learn was successful identification of all the reef fish species on Koh Tao, particularly the differences between species of grouper because they change color so often. Growing up to 120cm and found in the shallow reef waters of the Indo-Pacific, the roving coral grouper (Plectropomus pessuliferus) is perhaps the most common grouper found on the reefs of this island, but is also one of the most confusing to identify because of its constant and drastically-changing color patterns. I found this quite fascinating, but when I tried to look into the reasons behind these unique color markings on this particular species, I was met with not many scientific studies at all.

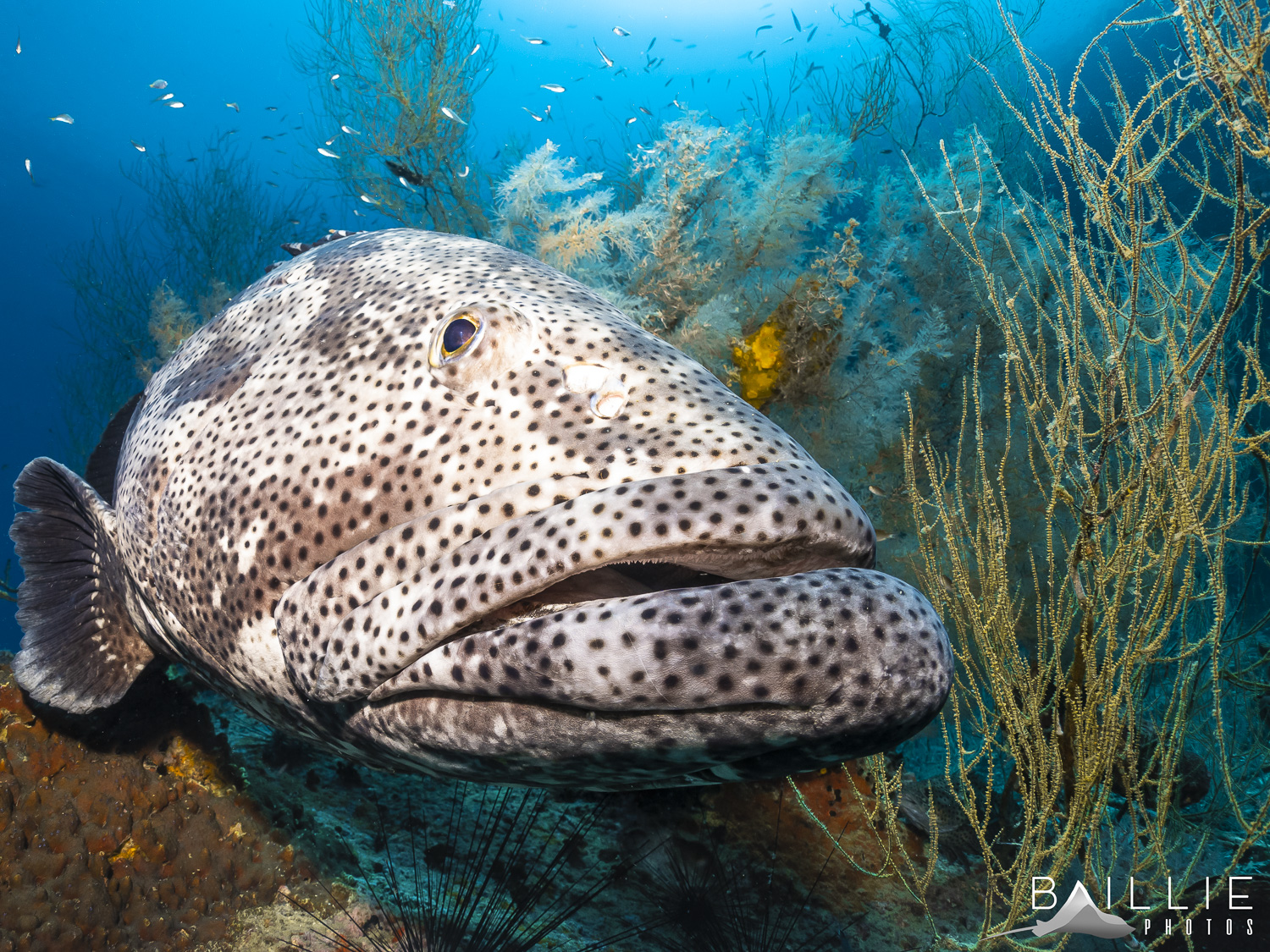

I decided to conduct a series of underwater surveys, noting the depth, size, and color of each roving coral grouper before beginning to watch it for the next 60 seconds. I noted the grouper behavior during that time period (hunting, hiding, resting, swimming, mating, etc) and whether or not its color changed along with these behavioral patterns. After the first few surveys, we were able to generalize grouper color markings into a few categories: dark brown/grey with blue spots, light grey with blue spots, and a rock-like black and white camouflage pattern with dark spots. Although the groupers were not always fully one color pattern, it was always a combination of one or more of these categories. For example, a grouper hiding beneath a light-colored branching coral may stay a light grey but display just the faintest of camouflage patterns to mimic the shadows of the coral above. What’s more, when groupers were lit with a torch, we discovered they were able to change the color tint of these skin patterns to match their environment. A grouper hunting around pink and red coral will tint pink and its fins will change to a slightly reddish color, while a grouper hunting schools of fish in a more pelagic environment will become very very light, tinting a greenish-blue to match the blue ocean and sandy floor surrounding it.

Moreover, it was extremely interesting for me to note a negative correlation between the more popular dive sites and the groupers’ reactions to divers in the water observing them. I was able to record much more behavioral and color-changing data at the less frequently dived sites, most likely because groupers weren’t as relaxed around divers and therefore had more of a desire to hide or swim away when being observed as well as a need to use camouflage and changing color patterns to do so.

When I began studying these fish, I was curious whether their color changing was conscious, depending on their environment and what they were doing within it, or if it was simply random and not under their control. It quickly became evident that their color markings and behavior were closely correlated and often a purposeful action. One example I observed was that of a grouper hunting alongside a moray eel. Although both are carnivorous and solitary predators, these two unlikely companions will often make use of the other’s complimentary hunting skills in order to ensure that prey cannot escape. I observed this particular grouper going so far as to mimic the exact color pattern of the eel when attempting to squeeze into hiding places only the eel could fit.

While more data and studies are required to come to a scientific conclusion, these observations we were able to make suggest at least an awareness, whether conscious or instinctual, of how color pattern and the surrounding environment can be strategically used to a roving coral grouper’s advantage in order to survive and thrive in these reef ecosystems.

Written by Maya Homicz, Marine Ecology and Conservation Intern at the Roctopus ecoTrust.